Contains major spoilers for The Zero Theorem and The LEGO Movie.

Well, I didn’t lie, exactly. It just took a little longer than I expected. I actually did write the main body of this post a while ago (hence the lazy Eurovision crack in the next paragraph), but it was a time when the film had already left UK cinemas, and very few people elsewhere had gotten the chance to see it yet. Anyway, it is now out on VOD in America, with a limited run in cinemas coming later this month, so now seems as good a time as any.

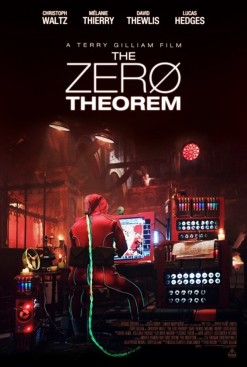

So, the importance of searching for one’s own meaning or purpose in life, in the face of an incomprehensible or actively hostile world, has pretty much always been a popular theme in film narratives. This year alone, Under the Skin, Inside Llewyn Davis, The Double, The Zero Theorem, Lucy and, yes, The LEGO Movie have all directly addressed this central existential concern. And they all draw upon the idea that it is up to the individual to negotiate their own meaning, because the world doesn’t have meaning beyond that which we impose – it is an absurdity. After all, we live in a universe that produced the Eurovision Song Contest.[1]

Incongruous as it may seem, The LEGO Movie and The Zero Theorem in particular share a specific blending of existentialist ideas with narratives that both evoke and parody mystical experiences.[2] Pat Rushin, screenwriter of Zero Theorem and a professor at the University of Central Florida, was inspired by the Book of Ecclesiastes, which he suggests “asks the major questions. What is the value of life? What is the meaning of existence? What’s the use?” All of which clearly chime with modern existential concerns, even while drawing from a Biblical source.

It’s explicitly stated in The Zero Theorem that the burned-out chapel in which Qohen (Christoph Waltz, of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained fame) lives was previously inhabited by Gnostic monks who had taken a vow of silence and, in a moment of ash-black comedy, he remarks that this vow led to their deaths in the fire. For sacrificing communication in the name of attaining true knowledge, the monks were punished (or, if you are of a particular frame of mind, rewarded) with death.

Qohen himself has suffered a severe existential crisis in his past. Having realised that he is ‘not special’, he awaits a phone call that will give him a purpose in life, a reason to be.[3] Because of his absolute belief in this phone call, in his own personal salvation, the sinister Management (Matt Damon, The Bourne Identity), declares Qohen to be the most religious man there is. This is why Management chose him for the task of unravelling the Zero Theorem, which will prove that eventually the universe will collapse in on itself, and therefore the fundamental pointlessness of all things. Which, according to Management, will be a valuable sales tool.

By curious coincidence, however, the method by which Qohen goes about attempting to solve the Zero Theorem is visualised by nothing other than the assemblage of blocks, which either form patterns or collapse into chaos depending on how successful Qohen is in his pursuit of the Theorem. This leads us smoothly into The LEGO Movie, of course.

In contrast to Qohen, LEGO everyman Emmet (voiced by Chris Pratt, rising star of Guardians of the Galaxy and the upcoming Jurassic World) is quite content at not being special at all. His single desire is to fit in with those around him.[4] The revelation that he’s supposed to be the ‘The Special’ who will save the world from the plans of evil Lord Business (who manages to be even more obviously sinister than Management) is profoundly uncomfortable to him, in a way that deliberately echoes the idea of the refusal of the call to adventure as defined in Joseph Campbell’s conception of the monomyth.[5]

Another prominent Campbellian theme is the idea of ‘death and return’, where the protagonist suffers a physical or metaphorical death and enters an ‘Other World’, with the goal of bringing back some divine knowledge or ‘boon’. It is, clearly, a mystical experience, and it makes an obvious appearance in The LEGO Movie when Emmet’s sacrifices his own life save the Master Builders from Lord Business. After Emmet ‘dies’, he pierces the veil of his reality, he gains true knowledge, and sees Finn (Jadon Sand) and his father (Will Ferrell, of the Anchorman films, not to mention the underrated Stranger than Fiction) as they really are, even if he doesn’t fully understand them. He is, after all, a tiny little LEGO man.

The story of the film so far is, therefore, simply an extension of Finn’s imagination.[6] This creates a curious inversion of the relationship between the human and the divine. Finn’s father is, after all, credited as ‘The Man Upstairs’, which is also how the inhabitants of the LEGO world refer to him. He is their demiurge, the creator of their world, and Finn is their messiah. Yet this is all ironised by the fact that Finn and his father are clearly just ordinary people, placed into the role of gods by their relationship with the LEGO world.

And now, to segue equally smoothly back to The Zero Theorem, the relationship between Finn and his father strikingly mirrors that that of Management and his son, Bob (Lucas Hedges, Moonrise Kingdom) in Gilliam’s film. Initially, Bob seems as misanthropic and selfish as everyone else in Qohen’s world, insisting on calling everyone else around him ‘Bob’ because he’s not even interested in so much as remembering another person’s name. Eventually, however, Bob is revealed as Qohen’s most loyal or, at least, most honest friend – the rest turning out to be pawns of Management. Of course, Management is pointedly not God, and Bob himself would make for a rather poor messiah. The relationship echoes the idea of a Holy Father and a Son of God, but Management and Bob are, in truth, nothing more than pale shadows of religious figures they resemble.

When Bob sacrifices his health, and potentially his life, to help Qohen, it comes across as tragically futile. And when, in their final confrontation, Qohen once again demands his phone call from Management, demands to be given his sense of purpose, the latter calmly (even smugly) admits that Qohen must have mistaken him for a higher power. Indeed, there is no space for a higher power in the world of The Zero Theorem. That’s largely the point.

The film climaxes with Qohen apparently forfeiting his being in the real world in exchange for the experience of a virtual reality where he is able to act as his own personal god, playing with the sun as like it was a beach ball. He does, in the end, manage to actualise himself, his apotheosis a metaphor for an escape from the whims of an absurd and uncaring system. But like the Gnostic monks who inhabited the chapel before him, it would seem that this escape comes at the cost of his material, physical existence, if not his life.[7]

But, in The LEGO Movie, something much more mysterious happens. Just as it seems Lord Business and The Man Upstairs are about to achieve their final victory, gluing everything in place so nothing will ever change ever again, Emmet intervenes in Finn’s ‘Real World’. He sees his own world as the toy collection it truly is, an entirely absurd thing that has no real significance – yet he never loses the sense that it’s important to save his friends. He draws Finn’s attention back to Emmet himself, back to the ‘Piece of Resistance’ which will stop Lord Business’s plan in the LEGO world, back to the story he has created. And it is through this story, through realising that his own son has cast him in the role of the villainous Lord Business, not in an act of cruelty or malice, but out of genuine confusion and frustration and love, The Man Upstairs finally attempts to connect with Finn.

As much as the film happily cribs from the Campbell playbook, the generic-ness of the main plot ultimately becomes a punchline when it is revealed that Vitruvius (Morgan Freeman, The Shawshank Redemption), the Master Builder who serves as Emmet’s mentor, just made up the prophecy of ‘The Special’ as a way to encourage people to fight against Lord Business.[8] In so doing, the film undercuts its own the narrative logic, establishing an equivalency not only between its characters, but between the two levels of reality.

Here, the created is allowed to change the creator. The material has power over the divine. This is The LEGO Movie, after all. Of course it’s a gleeful celebration of materialism, even as it deconstructs and parodies the consumerist/corporatist arrangement (the former embodied by Emmett and the latter by Lord Business). The film happily rejoices in the pop-culture spectacle of having Batman hang out with the crew of the Millennium Falcon, or Gandalf and Dumbledore standing side-by-side. Were this film to ask its audience (especially children) to put aside the simple pleasure provided by throwing together material cultural artefacts, to become as ascetic as the Gnostic monks, it would be hypocritical in the extreme.[9]

Instead, it’s telling us something else. That storytelling is, fundamentally, an existential act. It is the attempt to give meaning and shape to experience, to life itself. The story Finn constructs in The LEGO Movie is an attempt to give meaning to the rules his father has created – and, in doing so, break through them. Finn takes his father’s neat and ordered collection, pulls it apart, and reshapes its constituent pieces together into something new. And, in a moment of pure alchemical magic, this act of storytelling reshapes his own life.

Next Time: I don’t know, maybe the new Doctor Who? Yeah, probably the new Doctor Who.

___________________________________________________________

[1] This was timely when I wrote it, okay?

[2] Particularly, they seem to resemble or reference the Gnostic idea that the material world is a lesser realm created by an evil demiurge, or creative force, and that we should strive to escape it and reunite with the true spiritual world. Etymologically the term Gnosticism comes from gnosis, the Greek word for knowledge, specifically knowledge which descends from experience – in this case a direct mystical experience of the divine.

[3] There is clearly some kind of relationship, intended or not, between The Zero Theorem and Darren Aronofsky’s Pi (1998), in which Max Cohen is also trying to solve a seemingly impossible equation of cosmic significance, and regularly receives phone calls which address him by name, just as Qohen imagines his phone call doing. After a particularly bad hallucinatory episode, Cohen shaves off all his hair, which Qohen’s unusual appearance clearly echoes.

[4] Ironically, Emmet’s lack of any distinguishing feature or gimmick, his attempt to sublimate his identity completely into the consumerist community around him, is why his fellow construction workers find him vaguely uncomfortable to be around – he’s the guy who invites himself along to things that you don’t have the heart to say ‘no’ to.

[5] For the purposes of this post, I’m going to leave to one side critiques of Campbell’s observations, and instead just note that his concept of the monomyth, or ‘Hero’s Journey’, has without a doubt been extremely influential in the construction of Hollywood narratives, the most famous example usually given being Star Wars.

[6] Again, there a curious resemblances to Gnosticism. There, the creative demiurge is often conceived of as an ‘evil archon’ (no, not a Dark Archon, Starcraft players), a negative aspect of the totality of the divine, who denies the human spirit its freedom and connection to the spiritual world. In this cosmic schema, the role of Jesus is an emanation of the divine, an “aeon” or eternal spirit, who provides the way for humanity to escape the material and be reunited with its divine origins.

[7] Qohen’s fate is, indeed, rather similar to that of Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce, Pirates of the Caribbean) in Brazil – the proper version of Brazil, that is – where Lowry is left only with his fantasy of a life with Jill (Kim Greist, Manhunter) after she has been killed and he has been tortured into insanity.

[8] Vitruvius, meanwhile, is clearly named after a Roman architect, engineer and writer from the 1st Century BC. He authored De Architectura, the earliest surviving work on, well, architecture, surprisingly. It’s probably also worth noting that architect comes from the Greek arkhitekton – which happens to mean ‘Master Builder’. Phil Lord and Chris Miller knew exactly what they were up to when they were writing this script.

[9] So yeah, The LEGO Movie is basically Postmodernism: The Film. But for kids, who have always done this sort of thing earnestly, and without thinking. This is, in fact, one of the most interesting things the film points out, that the remixing of cultural references and symbols isn’t necessarily an affectation, but something that is actually fairly elemental to our experience of narrative.